Killing My Batman (Excerpt from "How to Kill Your Batman")

**Before reading this blog it is important to know that within the last few weeks my father has apologized. I will update my readers in the coming weeks and discuss “How to Save Your Superboy” in my soon to be released book How to Conquer Your Superman. **

How to kill your Batman is different for every male survivor. For me, it means learning to become a better man, husband, father, teacher, and mentor as a recovering male survivor of childhood sexual abuse.

When reading Tom King’s, Batman, the need to become a better man seemed to be a recurring theme in numerous issues. Throughout the series there were no perfect fathers, or father figures, but there were those who strived to be better men. For example, there’s a scene in Batman #6 when Alfred, dressed as Batman and driving the Batmobile toward a deranged Gotham. The butler talks to himself, as if to calm his nerves concerning the absurdity of what he is doing, about when he agrees to be Bruce Wayne’s Godfather. He says, before ramming the Batmobile into the former hero, Gotham:

Well, Thomas, allow me to be the first to say what an honor it is to be asked. For you, possibly, to entrust me with the care of Master Bruce. Well, sir, I am humbled. But of course the need for such care will never arise. It is not as if on some dark night you are going to just go walking down Crime Alley with Martha in her best pearls. That would be…absurd. But, if such unlikely circumstances were tragically to come to pass allow me to assure you that it will not be a difficult burden to bear. Bruce is such a good boy, sir, as you well know. Quiet and calm and yet still compassionate and curious. Caring for him will be more a pleasure than a chore, sir. A life of mild days reading books. Tranquil nights playing board games. Perhaps a charity ball now and then.

Afterward, Alfred jumps from the vehicle and confronts Gotham. While his actions are meant to bring a moment of comic relief, at any moment Alfred could be ripped in half, or disintegrated by the hero turned villain. Instead of running or refusing, the butler stood his ground and did something insane for his son, Bruce. His actions gave Batman the needed time to arrive and save the day.

Throughout this series, Alfred was more of a hero than Batman could ever be because the love he had for Bruce conquered his fear. By all intents and purposes, Alfred failed at raising Bruce. Rather than help the boy heal from his childhood trauma, he grew up to fight crime dressed as a giant bat. Although he did not succeed in raising Bruce, he did the very best he could, and continued to do the best he could as Bruce took on the role of Batman.

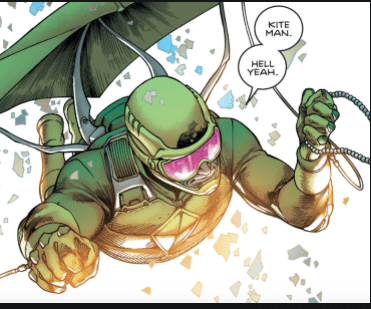

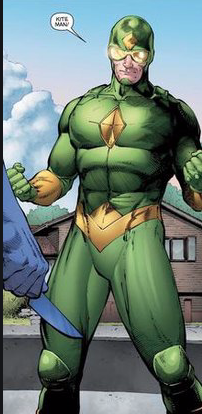

The villain, Kite Man, also comes to mind as a flawed, but still doing the best he can, father. During the “War of Jokes and Riddles,” Kite Man loses his son in Batman #27. Charles Brown becomes a pawn for Batman, the Joker, and the Riddler as each try to gain ground in the war. The casualty was Charles’s son, Charlie Brown, killed when Riddler sent a kite to the young boy with a rope laced in poison. The death of his son pushes Charles to become the villain, Kite Man.

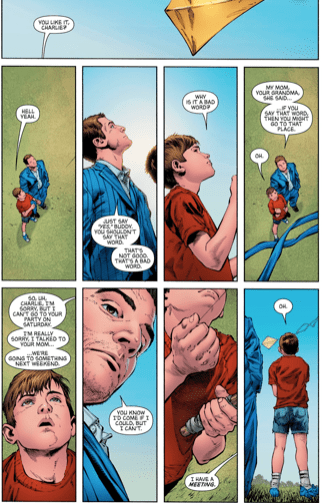

In no way was Charles a perfect father. In fact, he was kind of worthless as a father, but he still tried to be the best he could. In Batman #30, Charles narrates a conversation with his son, as he continues to be pulled from one side of the war to the other, like a kite in the wind. The conversation shows how Charles is viewed by other characters in the comic, but not his son.

Charlie:Daddy, can I tell you something?

Kite Man: Sure, Charlie. What’s up?

Charlie:Mommy was talking on the phone I don’t know to who.

Kite Man: Okay.

Charlie:And she said…well, she was talking about you, and…well, Mommy said you’re a joke.

Kite Man: What?

Charlie:Why did Mommy say you’re a joke?

Kite Man: She said that in front of you. That I’m a joke.

Charlie:Well, it was on the phone. That time. She said it before, too. That was probably

in front of me. She says it lots.

Kite Man: Your mother shouldn’t–don’t worry about that, Buddy. That’s not your business.

Charlie:But, Daddy…are you a joke?

Kite Man: Your mother didn’t mean that like it sounded. It’s fine

Charlie:It sounded like you’re a joke. Is Mommy a liar?

Kite Man: I mean, she didn’t — I mean, maybe she’s not a liar. No. Okay. Sometimes I am. I guess. I play with kites too much, and your mom is — she does a lot of stuff for you. So maybe she’s right.

Charlie:Are you a joke, Daddy?

Kite Man: I mean, look, buddy, here’s the thing. I try a lot of things. And I’m not always good at them. And when I fail, people laugh. I get it. It’s funny to watch. Like I’m slipping on a banana. And maybe when they watch and they’re laughing, they say, “He’s a joke.” I’m a joke. And so I guess I am. But what am I supposed to do? You know? I’m supposed to just quit? Just so they stop laughing? Just so they don’t call me a joke? There’s an old story. I ever tell you this? Like a guy is pushing this boulder up the top of this hill. And he’s cursed. So, like, every time he gets it right to the top, it rolls down. That’s the curse he never makes it. But he has to get it up, so he goes back down and gets it and does it over. Pushing it up again. Watching it fall over and over. Forever. That’s a joke, right? It’s funny. Right at the top, he’s happy and…whoops! Ha ha ha. Ha. Ha. And that’s me. That’s all of us. We’re all just pushing a boulder. Whatever we’re trying, we’re going to watch it fall, we’re going to hear them laugh. Right at the top of the hill. All of us. We’re all jokes. But the thing is, right, you got to laugh, too. It’s the only way. I mean, you got to laugh with them. Okay, I’m a joke. I’m a joke and I’m funny! Then you’re laughing with them. And if you’re laughing with them. Then at least your laughing.

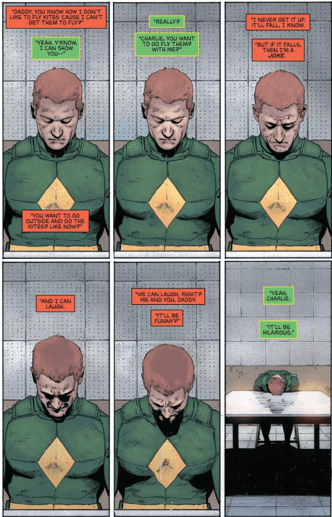

Charlie:Daddy, you know how I don’t like to fly kites ‘cause I can’t get them to fly?

Kite Man: Yeah. Y’know I can show you.

Charlie:You want to go outside and do the kites? Like now?

Kite Man: Really? Charlie, you want to go fly them? With me?

Charlie:I never get it up. It’ll fall, I know. But if it falls, then I’m a joke. And I can laugh. We can laugh, right? Me and you, Daddy. It’ll be funny.

Kite Man: Yeah, Charlie. It’ll be hilarious.

While flying the kite, Charles asks his son if he liked the kite. His son’s response was, “hell yeah.” Charles tells Charlie that “hell” is a bad word. The father explains to his son how his mother and grandmother said when he was a child that if he said the word then he might go to that place. Before dying in the hospital, Charlie asks his father if he was going to go to hell because he said the bad word. Before Charles could answer, Charlie dies. So, while it may seem to be a running joke that every time someone says, “Kite Man” the response is, “Hell, yeah,” it is actually in remembrance of his son.

No, Charles was not the best father, but the love of his son was evident. He tried. Failed. And tried again. When Charlie died, Charles became the villain, Kite Man, only to get close enough to the Riddler to avenge the murder of his son. In the end, when it was all over, Charles was lost. He continues as a villain only because he does not know what else to do. Again, a father doing the best he can with what he has.

Thomas Wayne telling his son, Bruce, to no longer be Batman so that he can happy. Bruce attempting to protect his sons from Bane’s wrath by telling them to leave Gotham until the trouble has passes. All of them make me wonder why my father, who claims to do (and did) the best he can, will not apologize for telling me to forget the sexual abuse committed by my sister from eight to ten-years-old.

Better Man

A number of years ago I told my father that for two years I had been raped by my sister (his daughter) from eight to ten-years-old. After explaining the details of the sexual assault he told me, “Forget about it. It’s in the past. The best thing you can do is move on.” Rather than cower and continue to harbor the secret I had been carrying for over twenty years, I responded with defiance and honesty.

I told him that I couldn’t forget. The abuse was something I had to live with every day and that it could not be forgotten.

He apologized, hung up, and did not speak with me for nine months. It was not until Daniel (my brother) told him that he needed to start talking to me that my father proceeded to text and talk with me as if nothing had happened. The illusion of normalcy was not something I could return to, so I asked my father for a written letter apologizing for abandoning me after I told him about my sexual assault. Rather than reply, he responded back via text. He said:

Okay son. I will respect your request. You are a grown man and able to make your own decisions. I’m glad you are doing better and I’m really sorry to hear about Sarah’s brother. Let me say this…I love my kids the same. You, Daniel, and _____are my life. I don’t love one no more or less than the other one. If I could take your hurt I would. I can’t so I can do only what I am able to do. But remember this. We can only start healing after we forgive. If I could change things I would. I’m sure your sister is hurting. I’m sure she had no intention of hurting you. Then or now. She has to live with the fact of what she did and face everyone who read your book and label her a rapist. This has to be really hard for her. I’m sure this has been really hard on you. I can only imagine how hard it has been. I know my kid and know you are strong. You can and will overcome this. It’s in the blood. No matter what you think, this too will pass. If you need me I will always be there for you. Don’t be a stranger. I don’t want you to one day think I missed out on a lot of my family’s life. She, Daniel, Tina (my mother) and me are your family. Love you unconditionally. Da

In Heroes, Villains, and HealingI analyze what this message means, the impact it had on me on me then, and the possible thoughts of my father after writing it. Since my father sent that message, I have yet to receive a letter of apology, but I have spoken with him.

This past August, Daniel (my brother) called to let me know that my father was having serious medical problems and not managing his diabetes. Photos of my father’s legs forced me to call in an attempt to tell him to stop being stubborn and go to the hospital. I lied and said I had already called an ambulance, but he still refused. After making a series of excuses about not having the money and going to VA Hospital, I became angry. Really angry! His pride and stubbornness pushed me over the edge. I began cursing, telling him how he did not prepare me for how hard life could be. Through tears, I told him how my wife and I had almost gone bankrupt attempting to survive paying for daycare and continue to work on the salary of two teachers. How fear of losing our house in Baltimore the same way I had last my home in Peoria made me stubborn, just like him. To survive we sold our home and moved to Ohio to be closer to family. I explained how we were living with my in-laws and attempted to articulate my anxiety, fear, and feelings of being a failure as a father and husband.

I yelled.

Screamed.

I begged for an answer.

Why would he not apologies for leaving me alone when I needed him the most? His response: “I can’t do something I don’t believe is right.”

My world stopped.

Until that moment, I believed, beyond a doubt, that maybe my father did not understand what I wanted from him to do to begin to repair our broken relationship. I thought that maybe be believed the text message he sent constituted an apology. His response proved that I was being naive.

There were no more tears as I heard him say, “It’s good to hear your voice.”

There was no more emotion as I heard him ask, “How are my grandbabies doing?”

I knew I had lost my father.

Afterward, I told him to take care of himself, and hung up the phone.

In the home of my mother and father-in-law, after selling my home, and ending the career and life I had made with my wife and children, I cried. I mourned the loss of my father. I mourned the loss of my childhood. I mourned the loss of my family of origin.

I have never felt so alone and like such a failure.

My father has often attempted to justify his actions told me, “I did the best I could.” I know now, this is not true. As a father, I look into the eyes of my daughters and my heartbreaks at the thought of not having them in my life. I love them more than I ever believed I could love another human being. If they needed my life, it would be theirs. My life istheirs. This is why I do not understand why my father will not apologize. If he loved me, if he did the best he could, he would do whatever it took to remain a part of my life. Instead, his pride, hypervigilance, and idea of manhood defined by the “boy code” keep him from saying three words; I am sorry.

I’m sorry for not showing up to your high school graduation.

I’m sorry I never paid the mortgage, ran away to Alabama, and you and your mother were homeless for two years.

I’m sorry the fights I had (physical and verbal) with your mother and brother ripped our family apart.

I’m sorry I didn’t protect you from being raped when you were eight-years-old.

I’m sorry I didn’t protect your sister when she was raped by Mr. Miller.

I’m sorry I told you to forget what happened to you.

I’m sorry you were raped.

I’m sorry I wasn’t a better father and husband. I could have done and been better.

These are the words I will never hear from my father. His Batman will live until the day he dies.Each day, my daughters and my wife kill a little more of my Batman. With each kiss, hug, and I love you, my Batman fades from existence. I attempt to conquer my hypervigilance to be a better father, husband, educator, coach, and mentor. Each day I fall short, but each morning I rise to try again. My Batman will never fully die, but I will always attempt to be a model for those striving to be, become, and know a better man.